Crafting Memory: Alessi's Funeral Urns

I returned from Milan's Design Week with my head buzzing from good conversations, pretty sights and delicious food. As in previous years, what touched me were not the slick booths in the gargantuan pavilions nor the glitzy brand-extending exercises of luxury houses (although I did like Loewe’s teapot exhibition, minus the long queues), but rather the smaller, often overlooked showcases that continue to linger in my mind a week later.

In 2023, it was a display of walking sticks at Triennale Milano (Lars Müller just published a book about it). This year it was The Last Pot, a series of funerary urns by Alessi (the crossed "last" representing a refusal of absolute endings).

Held at Biblioteca Ostinata, a small library next to the Statale University of Milan, it featured vessels for human and pet ashes designed by ten international designers including Michael Anastassiades, David Chipperfield, Michele de Lucchi, Audrey Large, Naoto Fukasawa and Philippe Starck. Visiting at lunchtime, I found myself nearly alone, able to admire each object in a calm space and chat with Francesca Appiani, curator of the Museo Alessi.

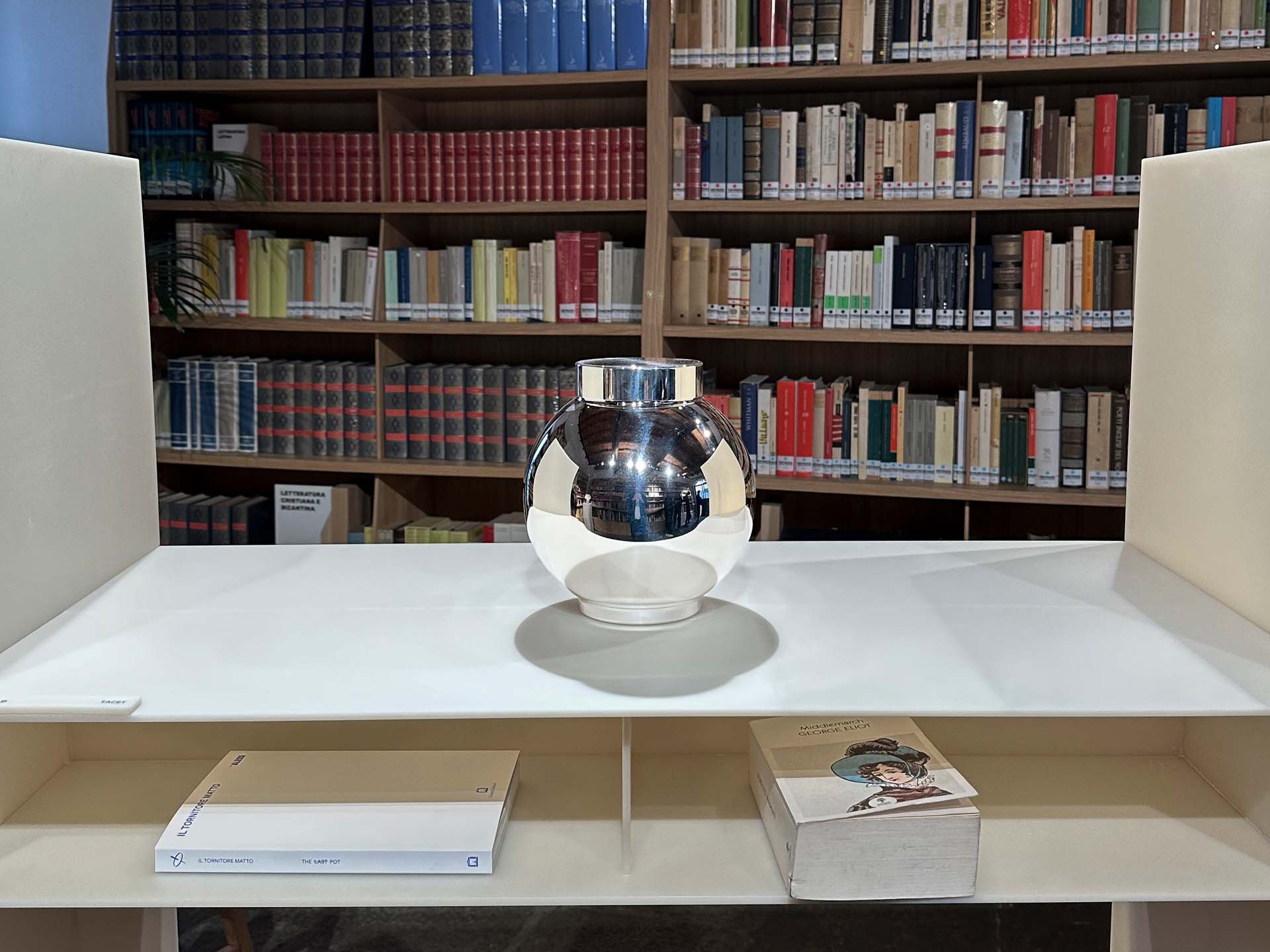

"Even when you die, you want to be at home." - Naoto Fukasawa

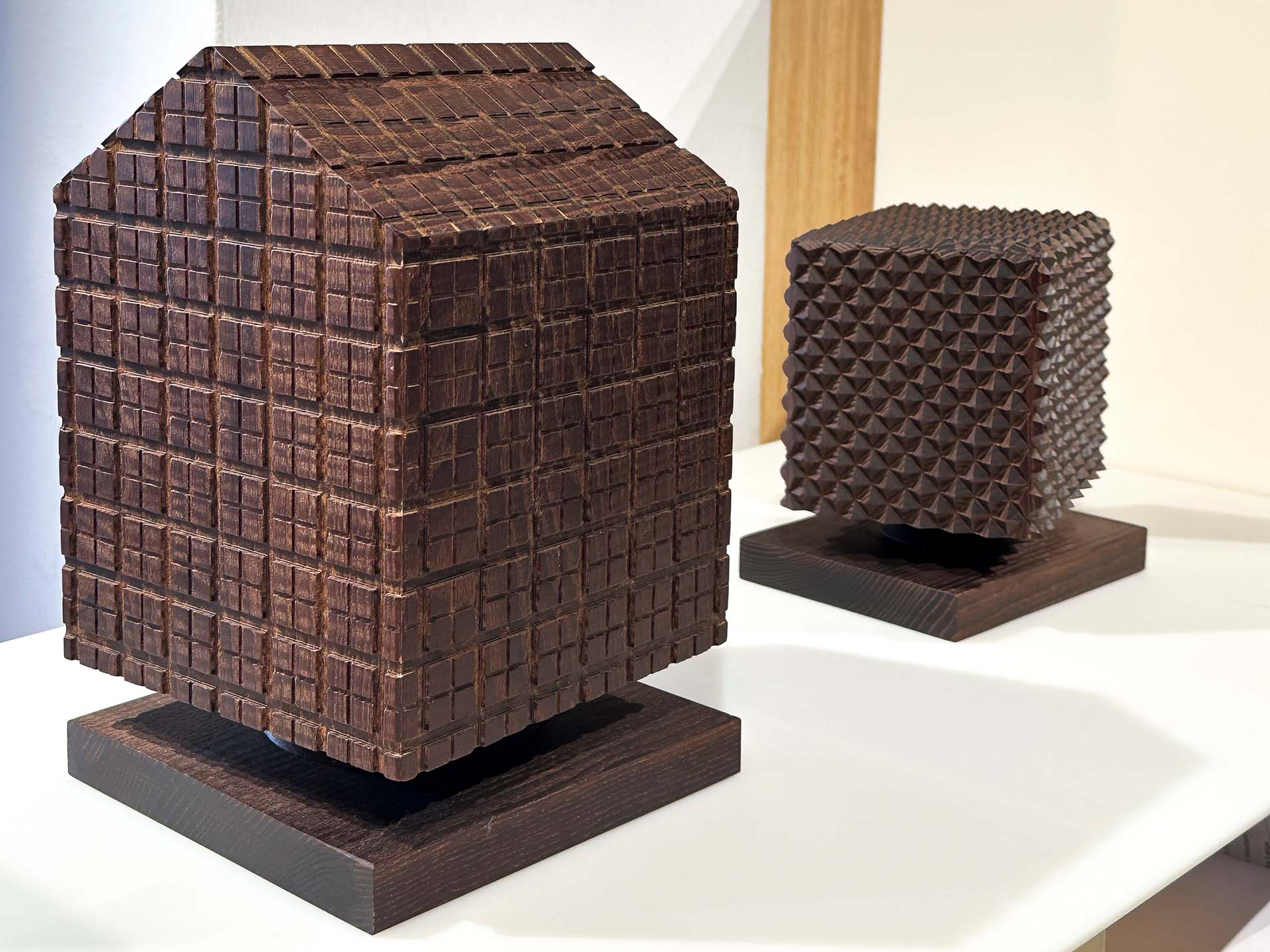

Urns by Naoto Fukasawa. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

Having a loved one's ashes on display at home is common in East Asian cultures like the Japanese Butsudan, but it's not so common to find urns as part of the home decor in the West. Alessi is famous for its kitchenware, like the outstanding 9090 coffee maker by Richard Sapper we had at home when I was a child. This collection was presented as a cultural project exploring what company president Alberto Alessi characterises as "borderline objects."

He writes in the accompanying book: "In essence, our entire journey has been about creating containers [...] Yet there was one container we hadn’t explored, a design category that had received surprisingly little attention: the funeral urn, the vessel meant to hold our ashes."

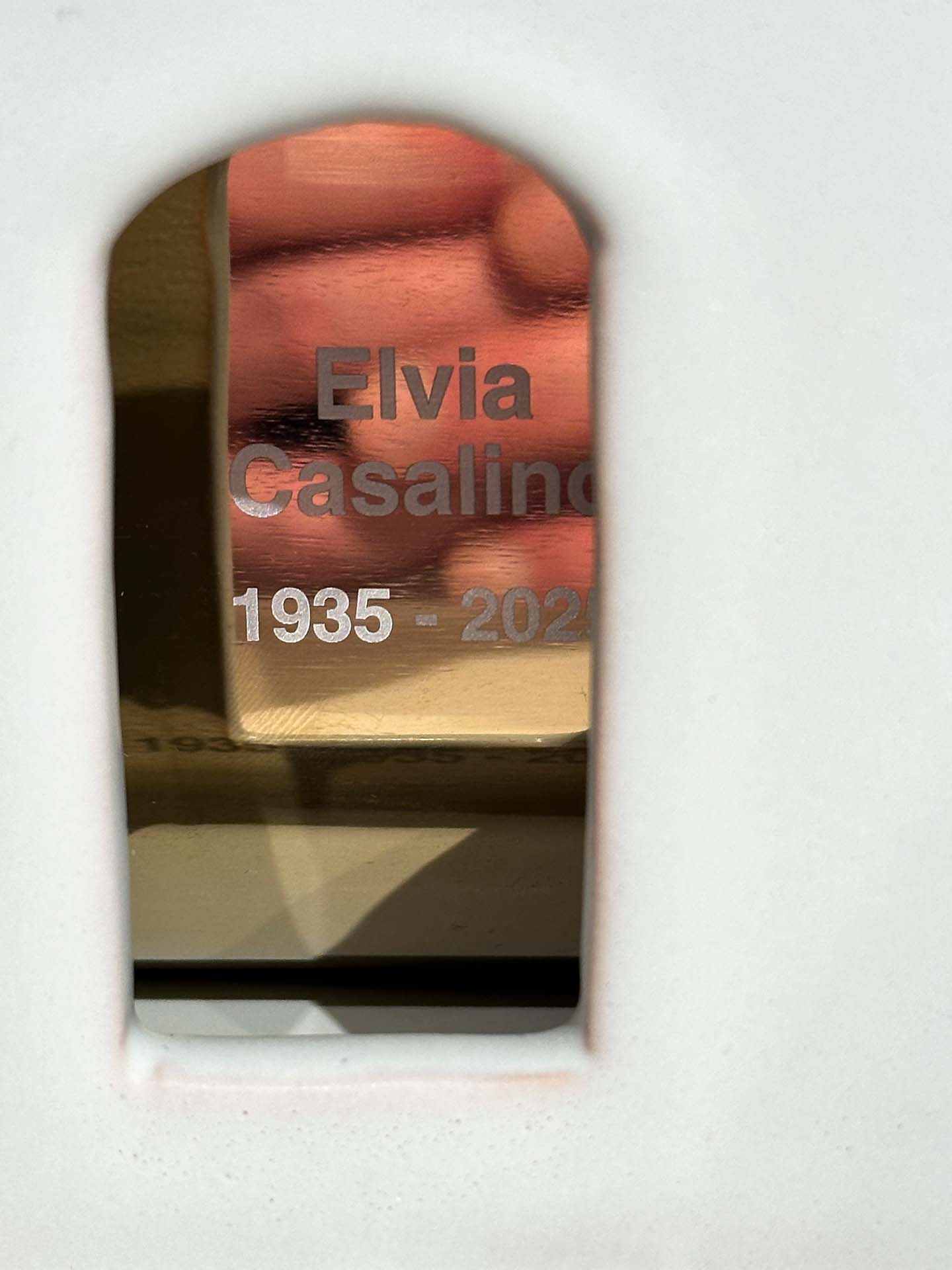

Left, urns by Michele de Lucchi. Right, urns by Daniel Libeskind, Michael Anastassiades and Giulio Iacchetti. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

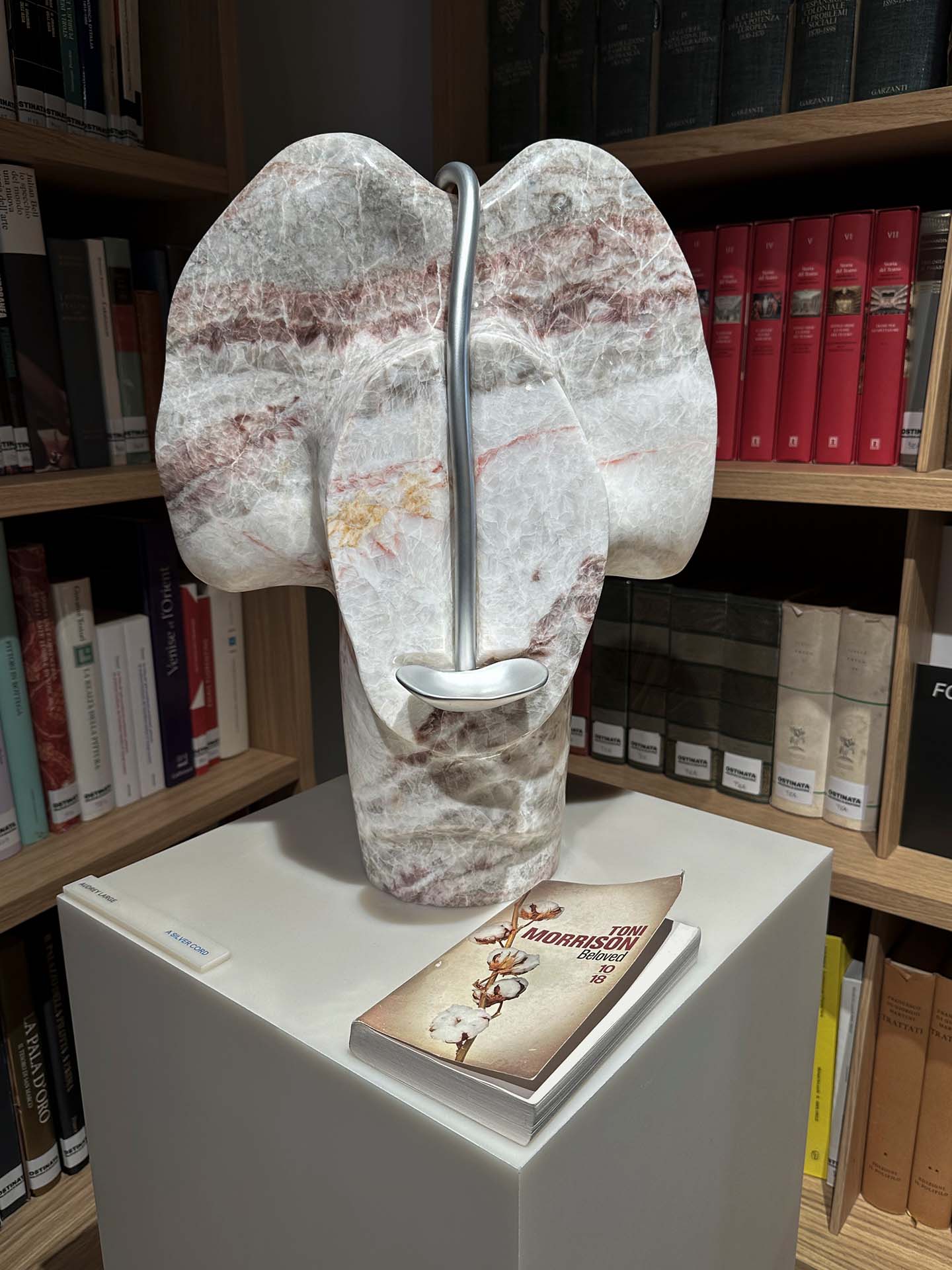

The urns were one-offs crafted from wood, ceramic, marble, metal and resin. De Lucchi's were inspired by his handmade models, using ash with yakisugi charring and wax finish. Large's example was modelled digitally following her hand movements, featuring a small metallic bowl for offerings.

Despite the taboo topic, nothing felt macabre. Cremation rates keep rising, Japan 99.97%, Britain 80.79%, Italy 38.16%. EOOS, the Austrian design team who proposed the project in 2010, approached it with pragmatism, developing a formula to estimate its potential:

Number of urns = population × death rate × percentage of cremated

Their analysis "revealed the lack of imagination and aesthetic quality in the existing urn offer", an assessment I unwillingly verified when my father was cremated. Over two decades ago, I received his ashes in a sealed plastic bag inside a kitsch wooden box. The process felt clinical. Though I lacked headspace then for considering anything better, I understand the appeal now.

While Milan's Salone worships spectacle, this modest exhibition tucked away in a quiet library posed questions about our final vessel with rare dignity. "These are not mere containers," wrote de Lucchi, "they are sanctuaries to honour the feeling that accompanies absence."

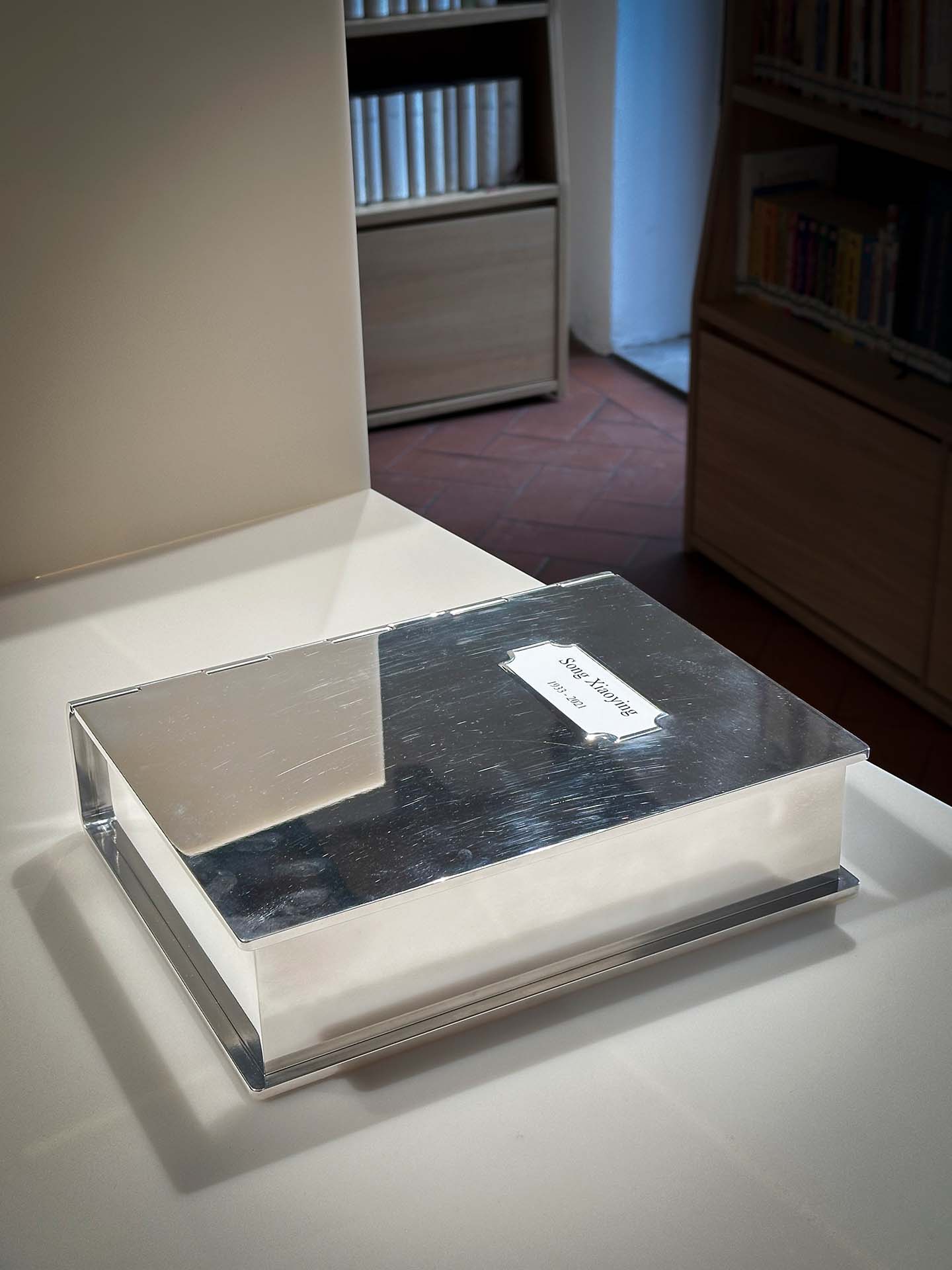

Urns by (clockwise from top left) EOOS, Audrey Large, Mario Tsai, Giulio Iacchetti. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco