Craftsmanship and Circularity Are One

When I’m asked about my interest in craftsmanship, especially that of Japan, I explain that at its core is the fact that circular principles are inherently baked in. Modern designers rightly focus on using sustainable materials, reducing waste, ensuring repairability, and promoting recycling. Japanese crafts go beyond this, intertwining material sustainability with social systems and the passing down of knowledge. Let me explain.

Materials

Before synthetic materials, craftspeople sourced directly from nature. They had to know when and how much to extract without depleting resources. While some materials, like minerals, can’t regenerate, today we can substitute scarce resources by mining waste products rather than virgin sources, such as extracting gold from old electronics.

Waiting for a material to reach its peak requires patience. Tango Tanimura is the 20th generation in a 500-year tradition of making bamboo tea whisks, ‘chasen’, in Takayama. He uses bamboo dried for two to three years, or soot-stained bamboo, ‘susudake’, from old houses. Much cheaper knock-off versions use bleached green bamboo that’s still humid, often packed with silica gel. Chasen by Tanimura-san perform better, last much longer, and are more beautiful too.

Longevity, Repairability & Upcycling

Quality, longevity, and repairability were once essential, especially for the working class. In Denmark, a country with a rich craft culture, families saved to buy well-made furniture that was passed down through generations. You’ll still find Danish homes with mid-century pieces like the Finn Juhl 108 chair or Louis Poulsen PH 5 lamp, which outlast most products today.

In Japan, broken items weren’t discarded. The Japanese aristocracy used ‘kintsugi’ to repair ceramics with ‘urushi’ lacquer sprinkled with gold or silver dust, while the poor embraced upcycling with ‘sashiko’, reinforcing cloth with visible stitching. 'Boro', patched up clothes that were once a sign of poverty, have now become fashionable, with brands mimicking its look to create artificially distressed garments (similar to the trend with jeans in the 90s).

Toolmakers

Artisans rely on a broader network of toolmakers. For many, their tools are an extension of their body. While all the attention falls on the craftsperson making beautiful objects, their work wouldn’t be possible without those who create tools of equal quality.

I recently met again with Noh theatre mask-maker Hideta Kitazawa, who lamented the retirement of Tokyo’s last blacksmith making the chisels he needed. He was in his 70s and the manual work was taking its toll, especially in a city prone to heatwaves with temperatures often exceeding 40°C. (Kitazawa-san asked him to make one final set of chisels before he retired).

Maker-Customer Relationships

Before online marketplaces and international trade became the norm, you often knew the maker of your products. If dissatisfied, you could return to them directly. Now, products might come from far away under questionable conditions, through transactions that are convenient but impersonal.

Kaikado makes my favourite tea caddies in their Kyoto workshop. They also repair caddies—some sold over a century ago—that customers bring back. Master craftsman Takahiro Yagi often travels with his tools to repair caddies for loyal customers in other cities, and I’m eager for his next London visit to touch up mine.

Passing Down Knowledge

Circularity also applies to knowledge. In my career, I’ve seen companies lose valuable information when team members leave due to poor documentation. There was no formal record of either how to do things or why certain decisions were made at different times, in what designer Andy Polaine calls “organisational amnesia.”

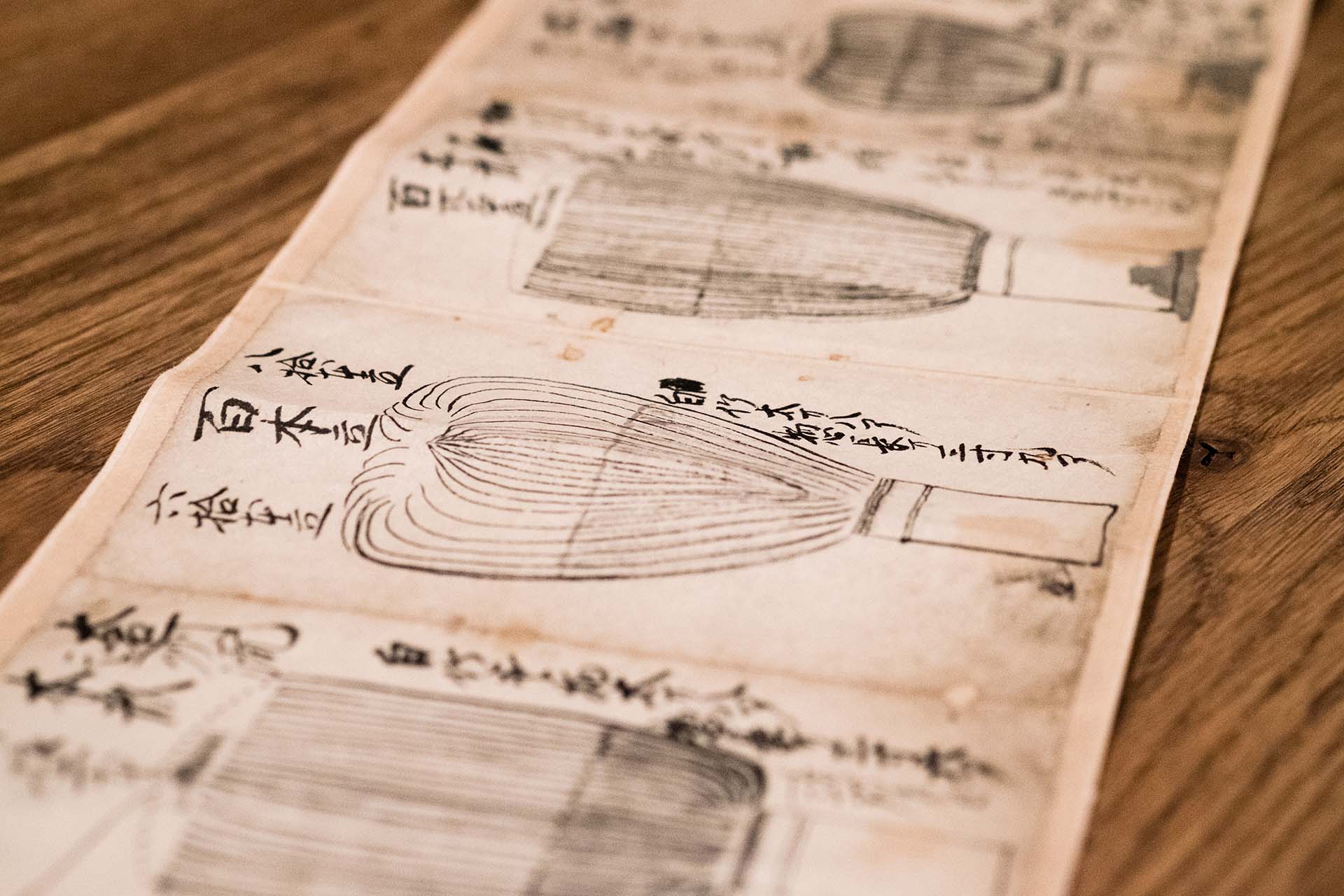

There are many ways to pass on knowledge from one generation to the next. Some are through formal written instructions, like in the case of Tango Tanimura (see the scrolls pictured below); other times, it’s oral or ‘from hand to hand’. In some cases, key information is withheld for the craftsperson to figure out themselves, thus adding a personal element. The Raku family of potters follows ‘Shuhari,’ a method of mastery through imitation, innovation, and transcendence. Here’s an excerpt from an article I wrote on how they keep their tradition alive:

“Shuhari establishes three phases to reach mastery. The first one, Shu, is to copy the master, to learn and follow the fundamentals of the tradition. Next is Ha, to challenge the received knowledge, breaking away to create something new by exploring new paths. Following and challenging are like a pendulum that swings back and forth. The third phase, Ri, is not automatic or easy to achieve. It’s about transcendence, the kind that frees the maker from the dualism of Shu and Ha. It's a leap onto a higher level, a new creative pursuit that allows the tradition to evolve without denying its essence.”

Good Business

Circularity isn’t just altruistic. Making good things that last while respecting nature and the community you serve can also be good business.

I thought about this when visiting the Vitsœ HQ in Royal Leamington Spa. It's a company that combines brilliant craft and design principles to make modular furniture systems, like the Dieter Rams-designed 606 Universal Shelving System, which has remained largely unchanged for the last sixty years. You can add and subtract different elements to change the configuration and purpose of your shelves, with almost complete certainty that the same pieces will be available decades from now. It’s not uncommon for children to inherit pieces from their parents.

Since 1999, they’ve been using simple wooden stillages for moving parts between multiple suppliers, and reusable cabinet bags to deliver their product to customers in the UK and Europe. This reduces packaging waste and saves the customer from dealing with massive cardboard boxes. Both containers are individually more expensive than their disposable counterparts, but considering they are easy to repair and remain in use for many years, it translates into significant savings for the company, and the environmental benefits are a bonus for us all.

Craftsmanship rooted in circularity not only preserves materials and traditions, it also fosters lasting relationships between makers, their tools, and the people they serve. In a world obsessed with fast production and consumption, I hope we can take inspiration from craftspeople to value creating with intention, care, and sustainability.

Thank you Leanne Cloudsdale from Concrete Communities for organising the visit to Vitsœ and to its CEO Mark Adams for welcoming us. Read more about Vitsœ’s history and Dieter Rams’ ‘Ten principles for good design’.

Like the content of The Craftsman? Share it with a friend! You can support my work by offering me a virtual coffee ☕️

つづく