Fabrico, ergo intellego

Enzo Mari was passionately opposed to consumerism and criticised mediocre objects not made to last. He believed that to truly appreciate the value of an item—like a chair or sofa—consumers needed to learn how to make it with their own hands, gaining a deeper understanding of what goes into creating a good product.

I make, therefore I understand

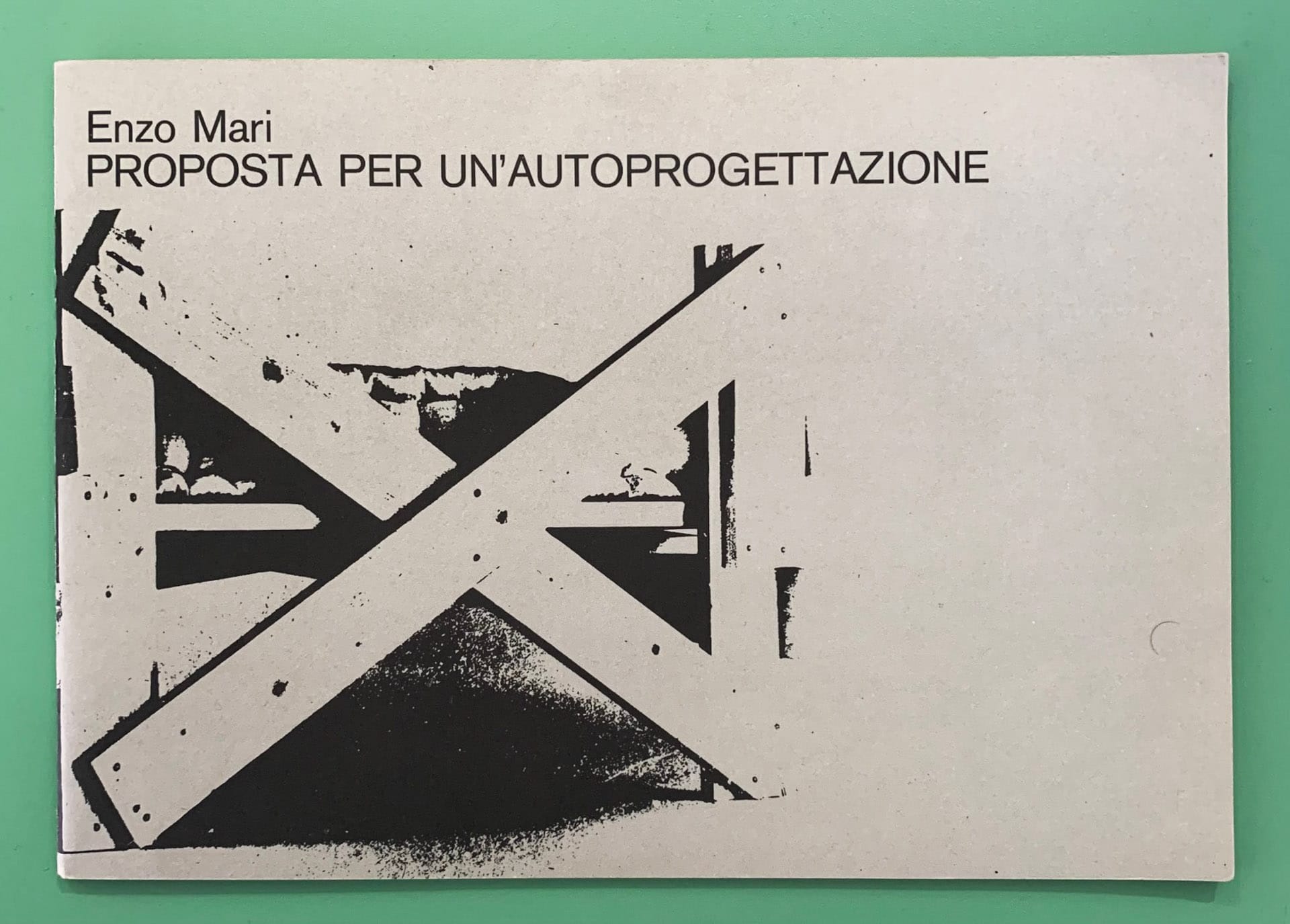

In Proposta per un’autoprogettazione (translated as Proposal for a Self-Design), a booklet still available for purchase, Mari offered a series of “easy-to-assemble furniture using rough boards and nails”. These designs taught everything from basic carpentry to finishing details. Paraphrasing Mari, everyone has used a hammer and nails at some point and would not be intimidated by the designs in autoprogettazione, which required no fancy materials or specialised tools—just things you could find at home or in any DIY shop.

I was fortunate enough to visit the exhibition at London’s Design Museum dedicated to Enzo Mari, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Francesca Giacomelli, just before it closed. (I had already missed it when it was shown at the Triennale in Milan between 2020 and 2021.) It featured a wide range of objects and interviews that highlighted the evolution of Mari’s career until his final days.

From the exhibition’s caption on autoprogettazione:

A radical proposal

Perhaps Mari's most overt attempt to democratise design and subvert the market was his seminal project Proposta per un'autoprogettazione ('Proposal for a self- design'). He devised instructions for the self-design of 19 models of furniture comprising only wooden boards and nails, using the simplest carpentry techniques.

Mari published them as a catalogue, available to any individual for the price of postage. Later, a few of the technical drawings were distributed through manufacturer Simon International.

Of the project, he said: 'In 1974, I thought that if people were encouraged to build a table, for example, with their own hands, they would be able to better understand the underlying thinking that has gone into it.’ Today this project is recognised as an important precursor to the open-source movement.

However, Mari considered the project a failure, as very few people—both users and critics—grasped its true purpose. In one video recording, he explained how the blueprints for Autoprogettazione were taken literally to create “designer objects,” and professional versions were sold at high prices—precisely the opposite of what he intended! Another caption explained:

He encouraged people to send photographs of built variations, but was disappointed that 'only 1% understood what the project was about. The majority praised him for the rustic aesthetic of the models or took it as an endorsement of DIY. A resurgent interest in the project led to the manual being republished in 2002.

The philosophy of learning by doing wasn’t unique to Enzo Mari. Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, created models and prototypes of his inventions, and architects, designers, and engineers have long used this practice to test concepts before finalising them. In the digital world, it's common practice to develop a “minimum viable product” (MVP) to test an idea or pitch it to others. Mari’s intention with Autoprogettazione was to make this designer-oriented approach accessible to everyone so that users could gain a deeper understanding of craftsmanship and develop a more discerning eye for products on the market.

In another caption, Francesca Giacomelli explains:

According to Mari, critical reflection is always based on hands-on practice, on direct experience, and for this reason he decided to involve the user of the commodity- the potential consumer -in the designing process and in the making of the object, materially experimenting the contradictions of design. Mari made precise choices: the production tools would be hammer and nails, which in his view were already part of everybody's culture because "everybody has at least tried to hammer ni a nail"; the material would be basic wooden boards; the technical culture would be carpentry, the easiest to learn in his view.

An unexpected result of visiting this exhibition was that it gave me peace of mind about my own curiosity and learning experiences. Throughout my life, I’ve enjoyed attending workshops on all sorts of topics, from visible mending to screen printing, wearable technology, terrariums, and many more I can’t even recall. While I genuinely enjoy the act of learning, it’s often followed by frustration, knowing I won’t be able to keep up or apply all of these new skills. What I’ve now realised —thanks to Enzo Mari’s philosophy— is that I’m driven by a curiosity about how things work and a deep appreciation for craftsmanship, which I can only fully grasp by trying it myself.

Learning by doing has also been vital for my professional growth. A few months ago, I wrote about making ceramic bowls at a 400-year-old pottery in Kyoto as part of my research for a book on Japanese craftsmanship. I wanted to (re)learn how to think with my whole body. Similarly, learning to build simple websites in HTML and design email newsletters early in my career gave me invaluable insight into managing complex web projects and shaping marketing strategies for the companies I’ve worked with since.

Making things first hand has taught me why attention to detail matters. Risking overindulgence in quoting those no longer with us, here’s a relevant one from Steve Jobs:

"When you're a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you're not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You'll know it's there, so you're going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through."

The same principle applies to growing your own vegetables, even on a windowsill, or learning to cook—it makes you value food more and waste less of it. The key takeaway? To appreciate things more, try doing them, even if you don’t aim for mastery. I now realise my curiosity doesn’t need to be frustrating; it deepens my connection and enjoyment of each experience.

Like the content of The Craftsman? You can support my work by offering me a virtual coffee ☕️

つづく