Kamon, the original logos of Japan

Traditions are living entities. The Hatoba family enriches and evolves the role of the Monsho Uwaeshi, the artisans of Japanese family crests, ensuring that the thousand-year-old craft of mon making remains relevant in the 21st century.

I come from an Italian family on my father’s side with a noble heritage rooted in the Renaissance through our ancestor Baldassarre Castiglione (1478–1529), and as such we have a coat of arms. It mixes elements like Baldassarre’s rampant lion and the Habsburg Empire’s double-headed eagle from his time serving Emperor Charles V.

Since Italy abolished nobility in 1946 and I was born and raised in Argentina, this legacy holds only historical value. But I have always loved our coat of arms. When I was twelve, my father gave me a ring with a simplified version on it, which I still wear often. When he passed away, I became custodian of the family ring with a more elaborate version, which I use on special occasions.

In 2022, I decided to create a new family crest that was my own, with a nod to the past while facing my present and future. My friend, technology and design journalist Nobuyuki ‘Nobi’ Hayashi, suggested that given my strong interest in Japanese culture, I could commission Shoryu Hatoba and his son Yoho (formerly Yoji), third and fourth generation Japanese family crest designers known as Monsho Uwaeshi.

The Origin of Kamon

Japanese family crests are called mon (紋, crest) or kamon (家紋, family crest). Inspired by natural phenomena, they emerged during the Heian period in the late 11th century as a visual shorthand for identity and artistry. Aristocrats used them on ox-drawn carriages to indicate ownership, rank and right of passage. By the Kamakura period (1185–1333), samurai clans adopted kamon in battle to distinguish friend from foe.

After Tokugawa Ieyasu unified Japan in 1603, establishing a long period of peace, kamon usage spread to townsfolk, who could have a family crest despite not being allowed to have surnames. Merchants displayed them on shopfronts, kabuki actors on costumes, and designs expanded beyond plants and animals to include tools, abstract patterns and wordplays.

During the period of rapid westernisation known as the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), people abandoned kimonos for Western attire. However, kamon persisted in other areas. Today, Japanese people still wear montsuki (meaning with mon) kimonos featuring crests for formal occasions. The Emperor’s kamon, a chrysanthemum flower, appears on every Japanese passport cover.

Although there are no official records, it’s speculated that Georges Vuitton’s iconic monogram for Louis Vuitton in 1896 might have been inspired by Japanese kamon, popularised in Europe by the artistic movement known as Japonisme.

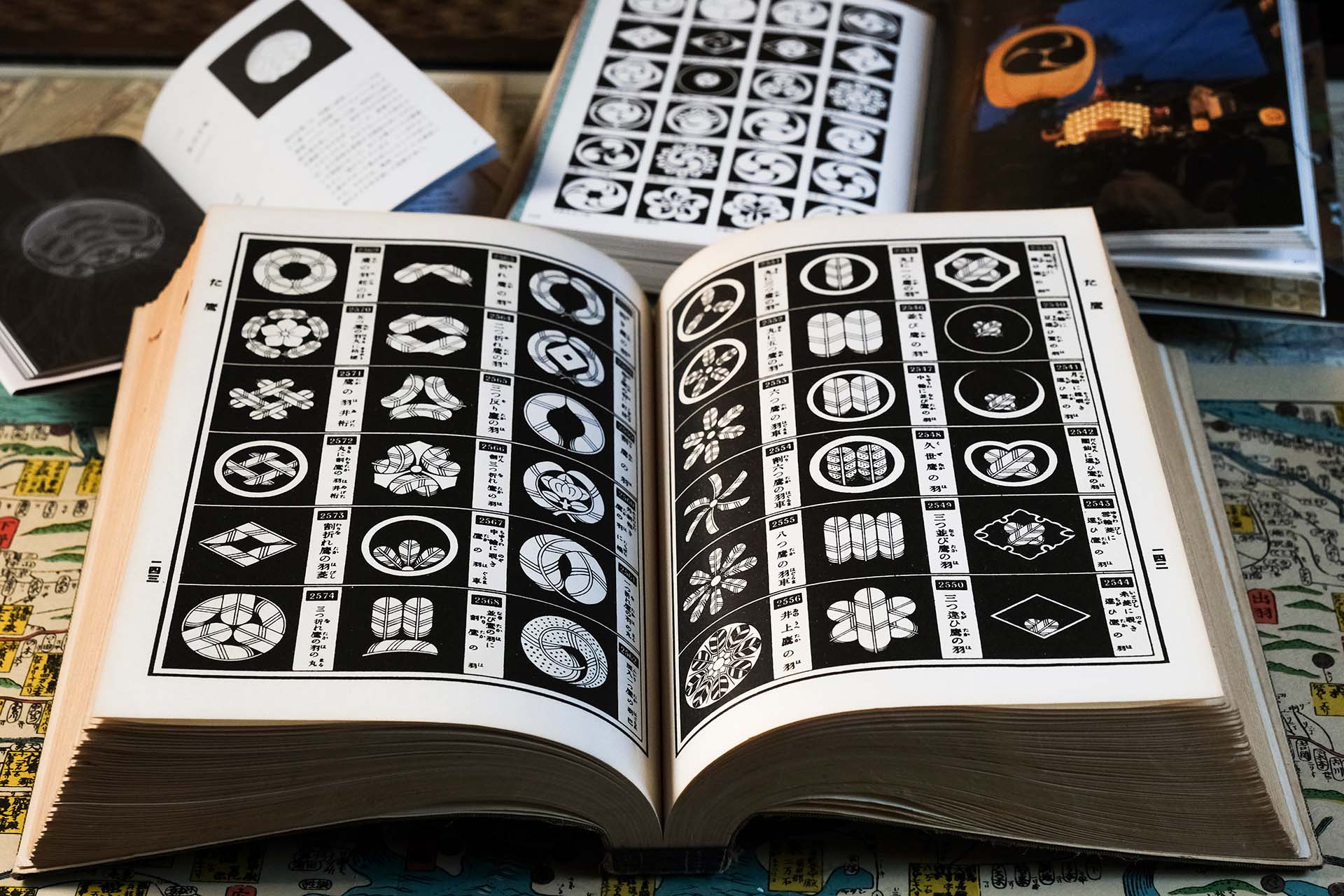

Kamon in catalogues and on the roof of Ryōan-ji in Koyto. Photos by Gianfranco Chicco

Designing My Kamon

Nobi introduced me to the Hatobas online. The process began with an interview where they asked about meaningful symbols like plants for vitality, animals for strength, or numbers with particular significance. I prepared a brief with the story of my current coat of arms and included a photo of a flower whose shape and smell represent home to me: Star Jasmine (Trachelospermum jasminoides).

Shoryu began apprenticing at 18 and has since created a vivid mental encyclopedia of mon. He estimates over 50,000 historical patterns exist, many documented in thick catalogues he consults for inspiration.

The reveal happened in November 2022 at their 90-year-old workshop in Ueno, Tokyo. After discussing their work’s origins, they presented their proposal.

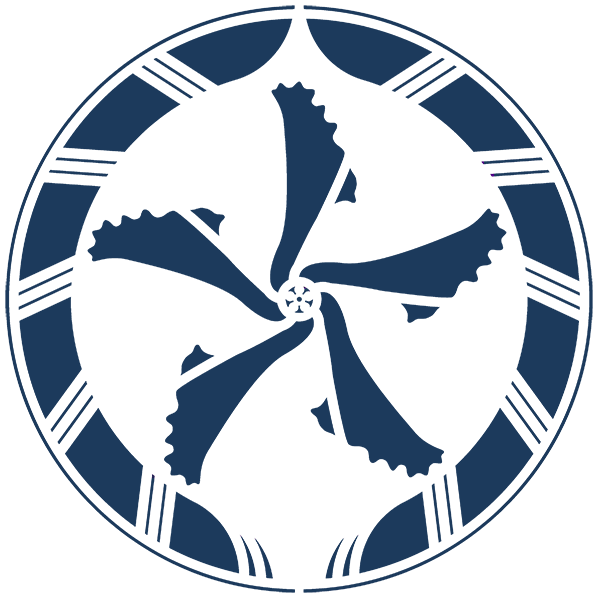

To create my unique kamon, they combined three elements based on our initial interview. They adapted the Habsburgs’ eagle wings using hawk feathers from the Takanoha (鷹の羽), one of the five major historic designs known as Godaion (五大紋). They thinned the feathers and added 17 lines for my special number. In the centre they drew a big jasmine flower, a design that as far as we know is new in the kamon canon.

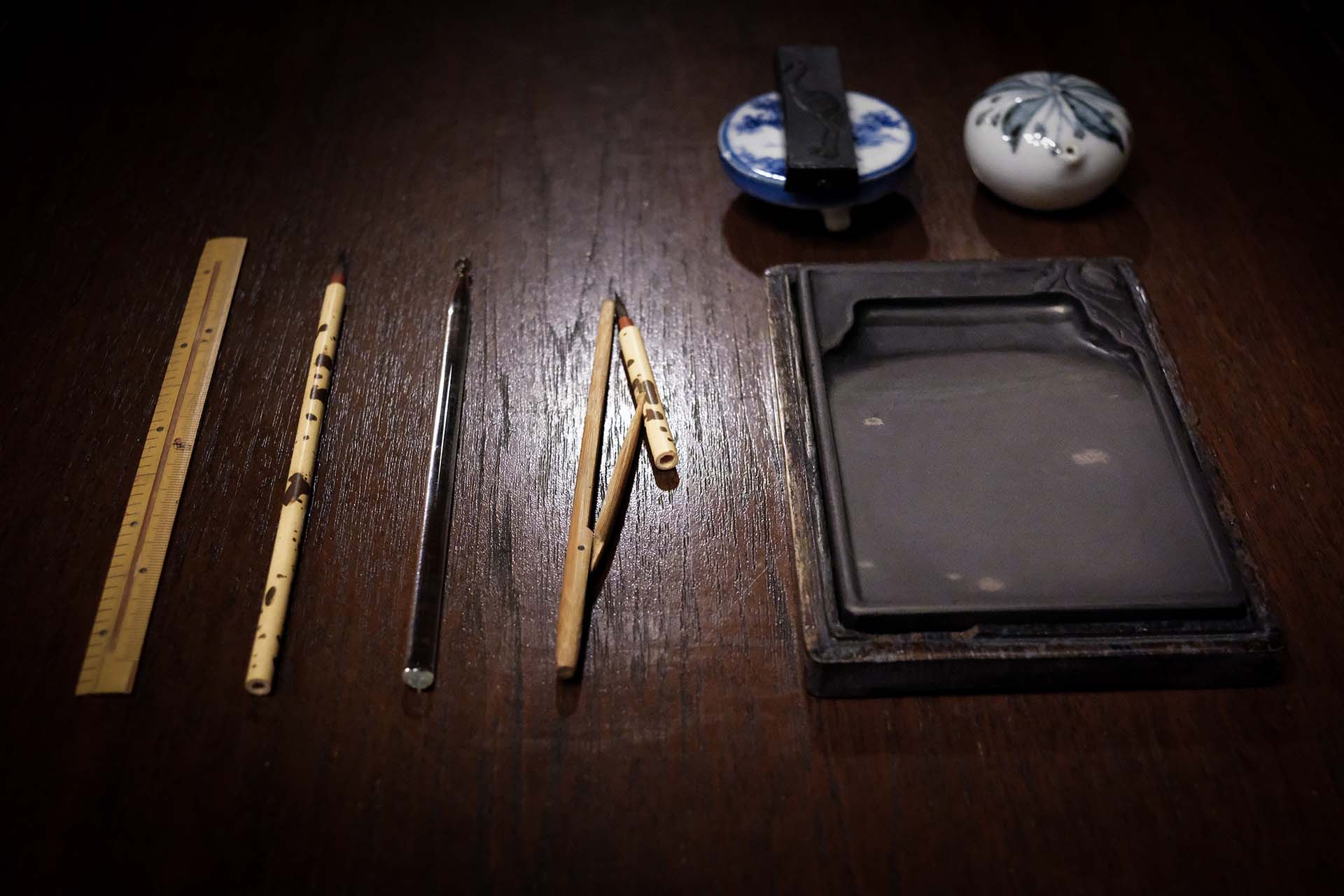

Though these motifs aren’t native to Japan, their application follows strict graphic design rules using just straight lines and circles using the seven “secret weapons” of Monsho Uwaeshi:

- Bamboo compass with brush tip (分廻し, bun-mawashi)

- Ruler

- Superfine brush

- Glass rod (for tracing straight lines)

- Ink-stick

- Inkstone

- Water dropper

Attention to detail is key. Yoho explained that “kamon designs have very delicate lines with constant thickness. For us, this and the gap between lines are most important.”

Evolving Tradition

The tools displayed in front of me at the workshop were those Monsho Uwaeshi have used for centuries, true for Kyogen too, the Hatoba family business since 1910. However, in 2010 they added a new arrow to their quiver: Adobe Illustrator.

Shoryu began using Adobe Illustrator at age 54 by pure happenstance when a client requested their work be delivered as an Illustrator file. Yoho, then 26, went to a local bookshop to purchase a how-to manual and installed a 30-day free trial of the software. It took more than a month to get the hang of it (Shoryu told me he needed a month and a half to master it) but after that they went beyond classic designs. This led to explorations like Mon Mandala patterns showing the hundreds of circles usually erased in traditional kamon. (Adobe visited the Kyogen studio after hearing about this).

Since adopting digital tools and facing declining demand for kimono applications, Shoryu and Yoho expanded into other design fields. This followed Shoryu’s father’s precedent of pioneering into art by displaying framed mon for the first time at the renowned Mitsukoshi department store in 1964.

Shoryu and Yoho are dedicated to preserving the essence of mon making. They sometimes encounter tension when clients request logo-like designs, as logos and kamon serve different purposes. While logos represent companies like Nike or Apple, kamon embody familial identity and tradition. Despite these differences, there can be overlap, as both can symbolize identity and heritage in their respective contexts.

This blend of tradition and modernity led to work with companies like Ferrari, where the Hatobas contributed to the Ferrari Roma in collaboration with Coolhunting by integrating Japanese aesthetics with luxury design elements.

Preserving Kamon for Future Generations

Kamon are more than decorative patterns; they are living symbols of Japan’s cultural heritage. Shoryu and Yoho see their work as both safeguarding and reinventing this tradition by applying its principles of symmetry, simplicity, and balance to modern contexts.

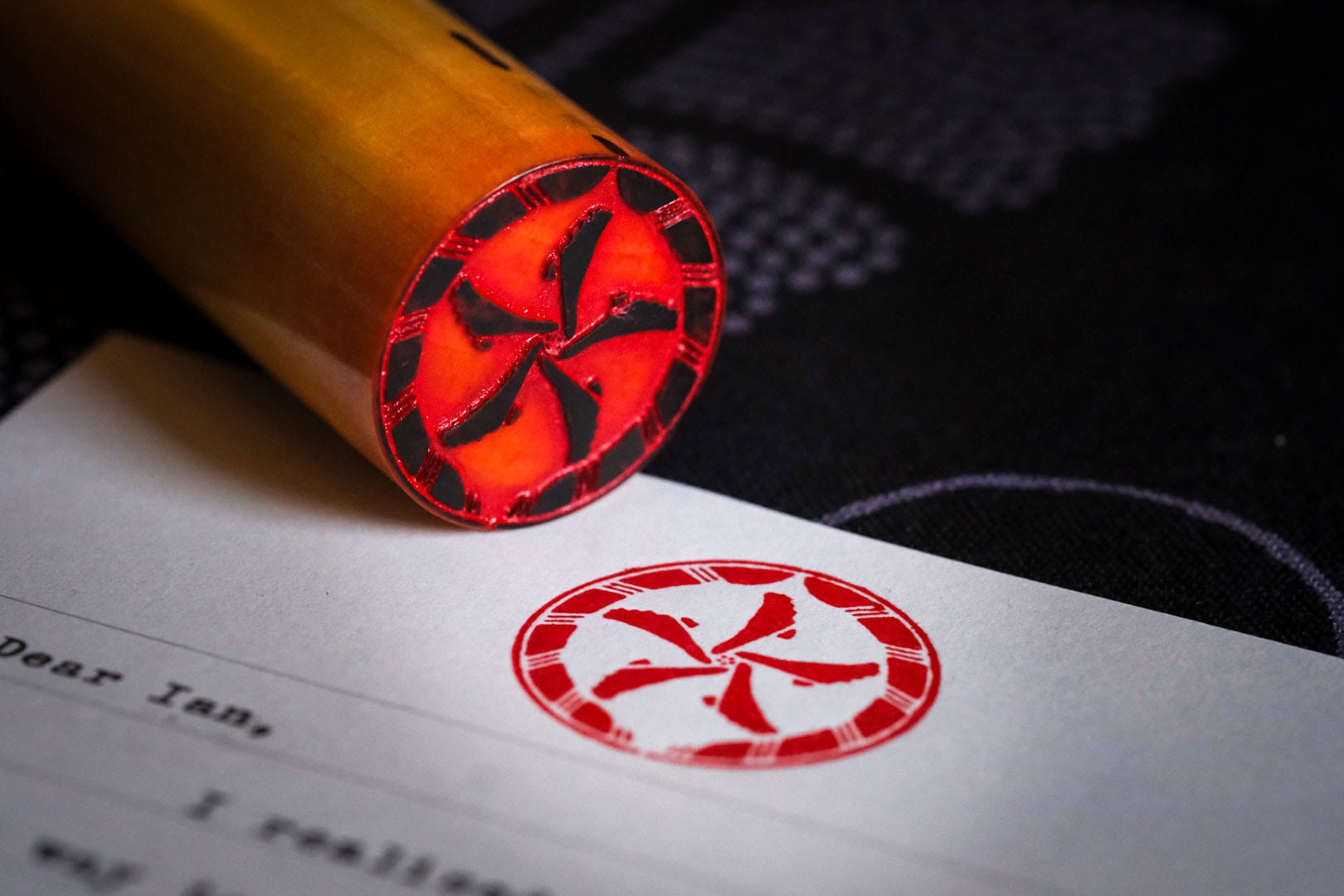

As for me, I’m very happy with my kamon. If you ask nicely, I might send you a letter or postcard stamped with it.

Like the content of The Craftsman? Share it with a friend! You can support my work by offering me a virtual coffee ☕️

つづく