Talking by making: pottery in the heart of Uji

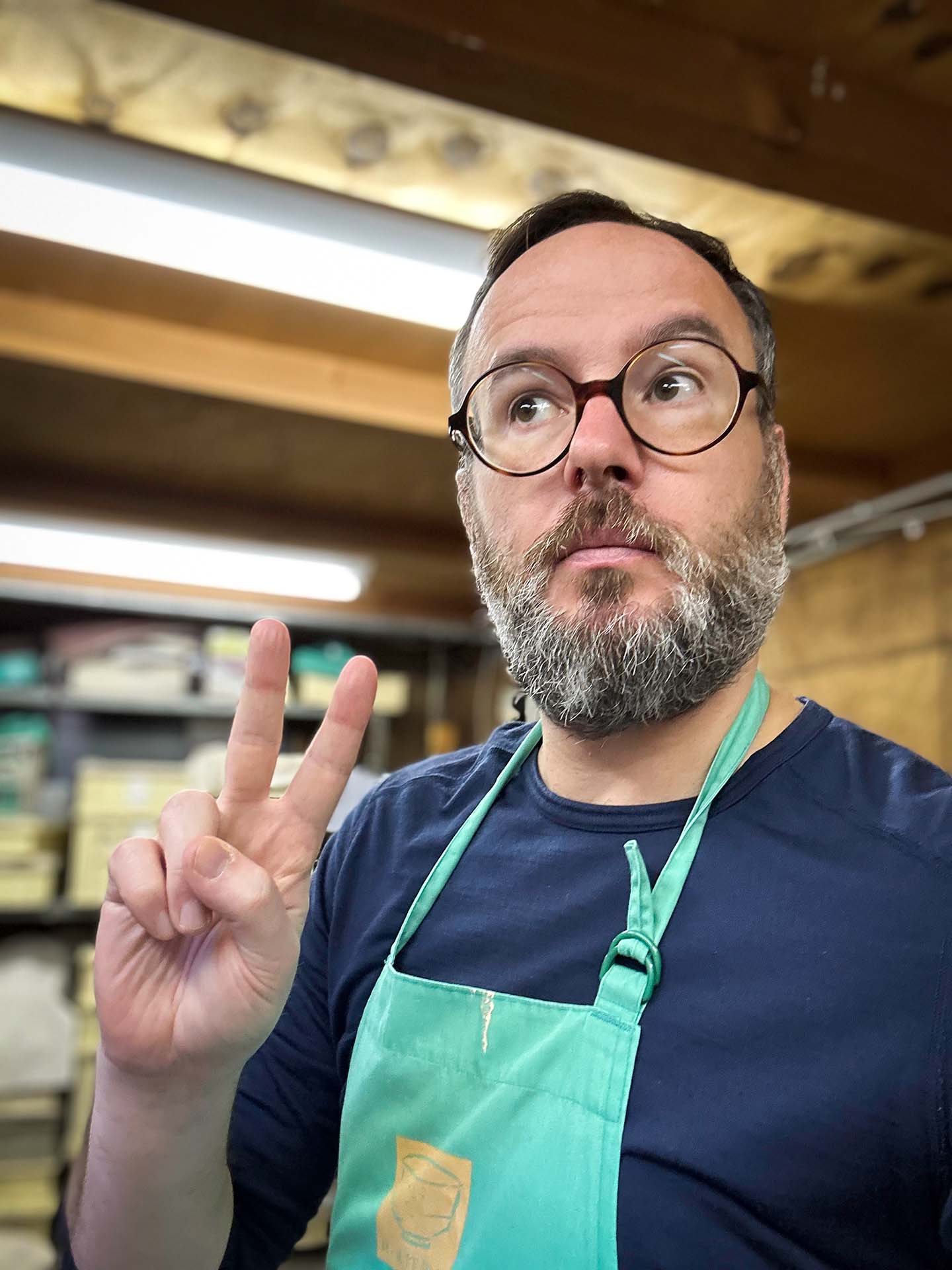

Ceramics and tea culture are both close to my heart so when Hosai Matsubayashi XVI invited me to practise pottery at Asahiyaki it felt like a dream come true.

In November 2023 I embarked on a research trip to Japan for my book on what we could learn from Japanese craftspeople, shokunin, to improve how we live and how we work. This is the second in a series which started with Talking by making: soba noodles in Tokyo.

Uji is a town on the outskirts of Kyoto that’s renowned for its tea, producing the best matcha in Japan and credited with inventing sencha in the 18th century (while matcha was reserved for the aristocracy, higher echelons of the warrior class and religious clergy, sencha - steeped green tea - was accessible to all). The Tale of Genji, a classic novel written in the 11th century by Murasaki Shikibu, is set in Uji. It’s also where the Asahiyaki Pottery was established 400 years ago under the patronage of the multitalented tea master Kobori Enshu. The current head of Asahiyaki is Hosai Matsubayashi XVI.

Ceramics and tea culture are both close to my heart so when Hosai san invited me to practise pottery at his workshop it felt like a dream come true.

Vessels by Hosai Matsubayashi XVI inspired by the Tale of Genji and Asahiyaki's Genyo climbing kiln

To Know and not do, is not yet know

I must confess that as the date to visit Uji grew closer, the prospect of working under the watch of a 16th generation master craftsman made me anxious. ‘Will I waste his time?’ I thought. I’ve been making wonky pots on and off for a couple of years without too much continuity. My mind understands how to make them but my body hasn’t retained much of the knowledge required to obtain the results I want. The good news was that this dichotomy between mind and body was exactly what I was interested in researching for my book.

When I first touched the local clay I found out it was much softer than what I was used to in London. Asahiyaki’s ‘hanshi’ clay is collected from the river and mountains surrounding Uji and aged for several decades before it’s ready to use. Very little water is required when handling it and to keep things running smoothly you just coat your fingers with the slip, liquid clay, that’s generated during the process.

The learning area at Asahiyaki

In pottery, ‘throwing’ refers to the process of creating vessels by manipulating the clay on top of a rotating wheel. In the UK it rotates in an anticlockwise manner, in Japan it does so clockwise. I was glad that I would be using a standard electric potter’s wheel rather than a more traditional kick-wheel which is operated with your foot. To make matters more challenging, throwing was done ‘off-the-hump’, a technique where you put a big pile of material on the wheel to make multiple objects in a row as opposed to using just the amount of clay required for a single pot. I was also encouraged to practise using very few additional tools in order to develop a better technique.

For most of my stay I was the only person in the area designated for students. Hosai san and his team, Suzuki san and Endo san, would give me guidance from time to time or answer any practical questions I might have. Otherwise I was left alone to do my thing.

Hyper-focus and flow

Sitting at the wheel for six hours during three consecutive days was conducive to feeling and thinking with the whole body. It’s as if my brain had moved from the inside of the head to the tips of the fingers, in direct communion with the clay. My basic Japanese vocabulary meant that instead of talking with words, any time I needed help or advice I would have to speak through what I was making.

I soon experienced the main advantage of throwing off the hump: it favours a state of flow. Not needing to stop and reset the wheel continuously means that you can carry on making with less interruptions. I wonder why it’s not common practice in the West.

The second day my nerves subsided. I was no longer embarrassed by the lopsided bowls that formed under my hands. I was getting at least one percent better by using each piece as feedback and carrying on those learnings onto the next one.

Very much like in Zen Buddhism tradition, cleaning plays an important part in the life of a potter. When I started at Asahiyaki, Endo san noted how much clay I was discarding (or getting onto my clothes), a sign of having poor technique. The better I became at making the less there was to clean. At the end of each session I measured the level of improvement by how much less messy my working station was. Although Endo san was not there to see it, I was proud that when my residency came to a close I had reduced the amount of wasted clay by almost two thirds!

Making and cleaning

An exercise in critical thinking

In the end I produced about two dozen pots, out of which I selected a dozen to be glazed and fired while the others would be destroyed and the material reclaimed. I was encouraged to be critical and keep only what I thought were the best pieces. It was an exercise in letting go: it’s hard to avoid being attached to what you make, but it would be unsustainable to keep everything.

Because there was not enough time to apply all the different combinations of glazes I wanted to try and fire the pots before I had to return home, I left notes with instructions to the staff that would finish them on my behalf. This provided further training in patience, a quality all craftspeople must have. If all goes well, I will see the result of my effort in the next few months.

Final pots, discarded pots

A lesson in slowing down

At a time when we’re overstimulated by the dazzling speed of digital technologies and ephemeral creations that overstimulate us from the neck up, pottery forces you to slow down and get your whole body and mind in sync. It’s humbling and keeps the ego in check. If you’re lucky, you might also carry home a new bowl, plate or vase to brighten up your daily life. (I do believe that eating on a well made plate makes food taste better!)

My visit to Asahiyaki provided invaluable work and life lessons which I hope to carry on, and practising pottery in Uji had other benefits too. Apart from the beautiful views and calming atmosphere, my lunch breaks were accompanied by delicious soba, tempura, curry rice and an incredible pizza that combined the best Italian technique with a Japanese twist. And of course tea.

Matcha and dango at Tsuen, the oldest tea house in the world, happy Gian and Pizzeria L'asinello

つづく