The genius of Raku Jikinyū

“He’s clearly a genius” one of the collectors in attendance at the exhibition told me a few weeks ago. However, the work of Raku Jikinyū was not always seen that way.

Jikinyū rejects labels like ‘artist’, ‘artisan’ or ‘potter’ and would rather be called a chawanya, a maker of chawan (tea bowls). Until 2019, he was known as Raku Kichizaemon XV. Born in 1949, at age 70 he retired from leading the 400 year old Raku lineage by passing on the head-of-family mantle to his son Atsundo (now Kichizaemon XVI). Jikinyū then moved out to the lush countryside of Kuta village, a mountainous area in Kyoto prefecture where he keeps making tea bowls with as much intentionality as ever.

Throughout his lifetime he has been called many things. When his breakthrough exhibition Tenmon (天問), ‘heavenly questions’, took place in 1990, a large number of visitors commented that he had single handedly killed the Raku tradition by stamping on it with self-indulgent bowls that were not good for chanoyu, the tea ceremony. Jikinyū also severed other ties with the past by rejecting the hegemony of the San Senke (三千家), the three main tea schools derived from the teachings of Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591), for many the greatest Japanese tea master that ever lived. The San Senke had become the gatekeepers of the tea world, dictating everything from the style, shape and value that tea utensils should have to the names they should carry.

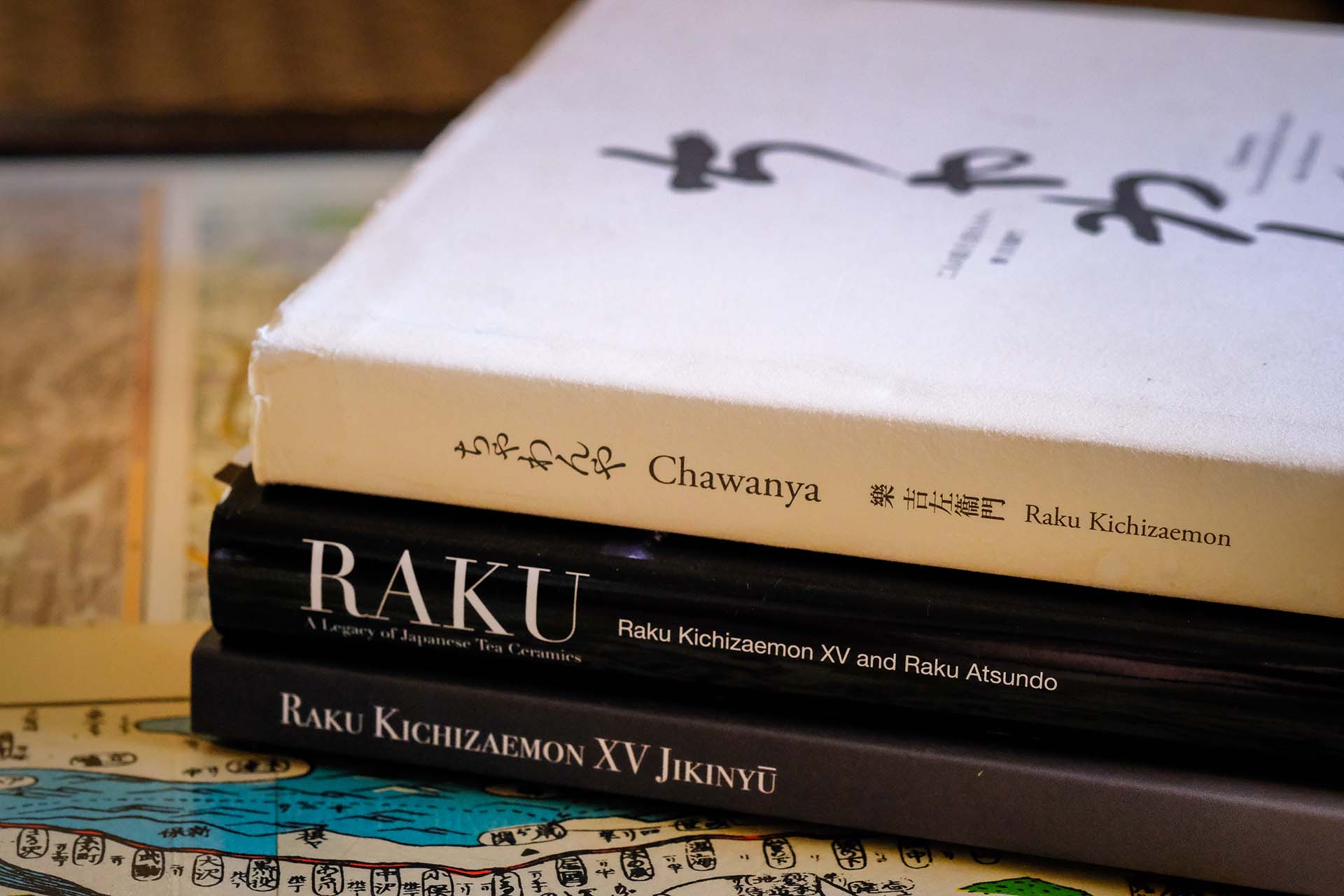

In his autobiographical book from 2012, Chawanya, masterfully translated into English by Dr. Rupert Faulkner and his wife Ando Kyoko, Jikinyū reflected on how chanoyu had become driven by novelty, market forces and “devoid of anything nurtured through the long history of tea.”

What, therefore, of the future of chanoyu? Without an underlying philosophy, without the questioning of nature, life and spirituality, chanoyu will degenerate from something extraordinary into a hollow form of demotic Japanese style tea time entertainment. The essence of tea is not to do with liberty of form but the choosing of constraints from out of which true creativity and freedom spring.

Jikinyū went on to describe the frenetic fervour that possessed him during the time of Tenmon:

The distorted rim rises to a spike. My mother, usually sympathetic muttered with a sigh ‘Why can’t you smooth out the mouth with an extra stroke or two?’ No way, I thought. Was it arrogance? Something wild and fiery was erupting inside me. Red hot and glowing in the darkness of the universe. ‘That patch of red, it looks like blood’, was the criticism. That very blood began to flow out of me. Searching urgently for someone who would understand. There must be others who bleed like me. All I want is for this teabowl to find its way to you. War is declared, for a friend yet to be found.

The foot of the tea bowl is so subtle that it seems to be floating.

Back to the source

What many see in Jikinyū as an uprising against the powers that be I see as him returning to the essence that motivated the original Raku potter, Chōjirō (?-1589), who started it all when Rikyū challenged him to create vessels that would better reflect the essence of wabi-cha, an understated kind of tea practice that emphasises modesty and subtle imperfections in contrast to the lavish, shiny and perfectly symmetrical preference of the time. The black bowls that came out from Chōjirō’s workshop were akin to rebellious punk music and some say that this and other transgressions were the reason why the Japanese de-facto ruler of the time, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, ordered his tea master (Rikyū) to commit seppuku, ritual suicide. (In a recent webinar with Joi Ito we discussed Rikyū’s rebellious spirit).

In Chawanya, Jikinyū recalls how during an exhibition in 1988 at the Raku Museum commemorating the 400th anniversary of the death of Chōjirō he had an epiphany that would mark the resolve of his work from then on:

Each day, after the museum closed, I wandered around the gallery. Time and again I found myself stopping in front of the same bowls. As I looked at them I felt some inexplicable feeling rising up inside me. Ōguro, Muichimotsu, Mukiguri, Ichimonji… This was when I got to know Chōjiro and through him to encounter Rikyū. I couldn’t suppress my emotion as tears welled up inside me. Through the small and quiet volume of the teabowl he lay waste in an instant to the values of society. He infused his bowls with an intense creativity that broke all accepted norms. Can you imagine how radical Rikyū’s philosophy was and how it led to his being forced to take his own life, how the uncompromising stance of his creativity took the form of an unavoidable destiny?

New work, same spirit

Jikinyū's latest work is currently on show at the Annely Juda Fine Art gallery in central London until 6 July 2024 (don’t miss it!). It features 15 ‘Black Rock and 15 ‘White Rock’ tea bowls that Jikinyū made in response to the music of Alban Berg (black) and Toru Takemitsu (white).

When I entered the room the energy of the pieces was palpable. Jikinyū himself was standing there, surrounded by guests, emanating an aura of calm transcendence beyond labels and judgement. After David Juda and Japanese Ambassador to the UK Hayashi Hajime offered some introductory words, we, the audience, looked at Jikinyū for a follow up speech but instead he just smiled. There was no need to add anything. The objects were already speaking loud and clear.

I visited it three times. The first one was too crowded to enjoy it properly. During the second one I was practically alone and benefitted from the sun beaming through the gallery’s skylight. The third one was to listen to a discussion between Dr. Faulkner and Tim D’Offay, the owner of Postcard Teas who has been a kind guide in my learning journey regarding Japanese ceramics. Seeing them handling the bowls, each one costing fifty to sixty thousand pounds, sent a chill down my spine.

The thirty tea bowls are massive, larger than any other Raku chawan I have ever seen. If you consider that clay shrinks between 10 and 20% it means that they were even bigger when Jikinyū was sculpting them. They will hardly - if ever - hold any tea. Collectors consider them objets d’art rather than cups to drink from, which is a pity but understandable given their quasi-architectural build. I asked a friend in Japan who moves fluently in serious tea circles and he confirmed that one Yakinuki-type chawan by Jikinyū did indeed show up at a recent gathering. (Yakinuki is a technique where the bowls are fired one at a time in a small kiln for about thirty minutes while the maker and their assistants frantically operate the bellows to raise the temperature quickly to up to 1,200 degrees celsius).

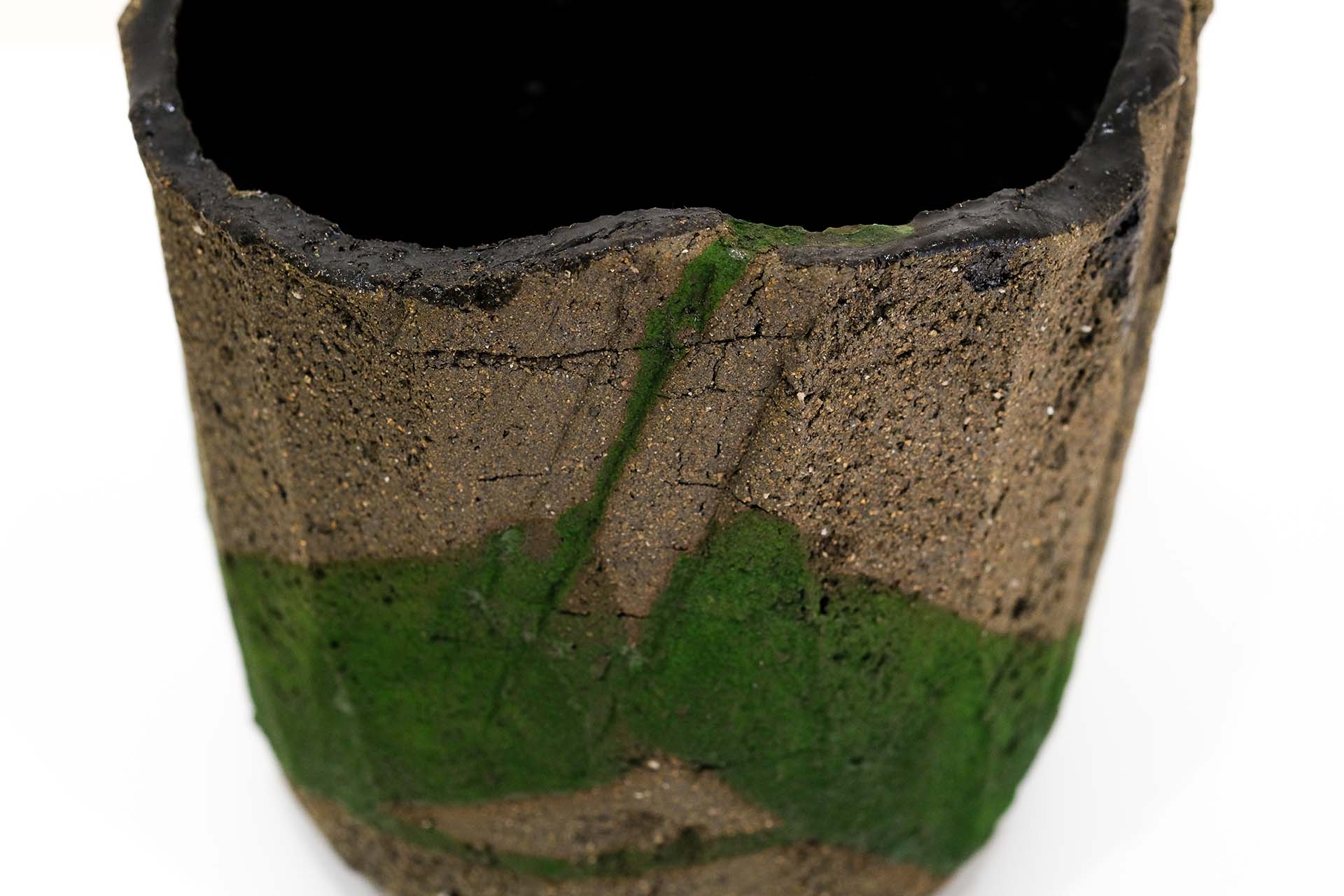

The Black Rock bowls have a military feel, in part because of the green and brown colours that adorn them and the groggy roughness of the clay. The bowl called ‘Tan (things that exhaust themselves by pushing themselves to the limit)’ pictured at the top of this essay has a chevron-like decoration that reminded me of the sleeves of an army officer.

The white ones are made of porcelain, another departure from what’s expected within the Raku tradition. They are also big but with gentle curves and markings in brilliant hues of blue and purple. The walls squeezed in an oval shape reminded me of a conch, with the narrow sides inviting you to drink from them.

The 'White Rock' tea bowls have gentle shapes and colourful details.

The music of Alban Berg and Tōru Takemitsu has influenced how Jikinyū finished these bowls. The former a proponent of the avant-garde of the early 20th century, the latter a mid-century master of timbre and its relationship with silence, Jikinyū’s describes the effect they had in his work in the exhibition catalogue published by Annely Juda:

When I started working on my Rock tea bowls for this exhibition my inclination was to work with blackness. The results - metaphors for what lies beyond language and the other side of silence - were quieter than my other recent work. By contrast, my White Rock tea bowls were experiments in the very opposite direction. I left nothingness behind me and sought to recapture beauty. Colours gushed into empty white space. I made these more expressionistic tea bowls not in response to Berg but in homage to Takemitsu. His world is one in which a single sound rings out in a white void.

Seeing Raku Jikinyū’s most recent creations sent me into a rabbit hole of exploration of his legacy through books in my shelves and those of Tim D’Offay. Jikinyū is not just an accomplished chawanya but also a profound philosopher, poet and photographer. His words moved me as much as his bowls. They invited me to pierce through the surface of the establishment to pay more attention to the essence of the things we do. It’s unlikely I’ll ever be able to afford a Raku tea bowl. If I’m lucky, I’ll be invited to drink tea from one of them sometime soon. For now, my only consolation are these books - and a lapel pin I got during a visit to the Raku Museum.

Last year I wrote about Shuhari, the philosophy that the Raku family uses to pass on knowledge while navigating generational change.

All photos by Gianfranco Chicco.

つづく